A new study has found that bowel cancer patients under 50 often experience delays in diagnosis, despite rates of bowel cancer markedly increasing in this group in recent decades.

Despite the rate of bowel cancer almost tripling in young Australians aged 15-24, and one in 10 new bowel cancer cases occurring in people under 50, new research shows that younger patients take longer to get diagnosed, and are more often diagnosed at a later stage in the disease.

Research published in the BMJ Open and BMC Primary Care by a team headed by Dr. Klay Lamprell, from the Australian Institute of Health Innovation at Macquarie University, is the first to investigate advice from people with early-onset bowel cancer on managing health service barriers to diagnosis.

“Our research found that some younger people spent between three months and five years seeing multiple doctors, some making ten or more visits to their GP before they were diagnosed,” says Dr. Lamprell.

She says that because bowel cancer typically affects people aged over 50, doctors may shape their diagnostic practices around low suspicion of bowel cancer even when symptoms are ongoing and worsening in younger patients, despite bowel cancer rates climbing by 266 percent in 15 to 24 year olds over the past 30 years.

Since 2006, Australia’s National Bowel Cancer Screening Program has mailed a free test every two years to all Australians aged 50 to 74, reducing bowel cancer mortality by an estimated 40 percent and leading to far earlier diagnoses.

Australians aged under 50 years are not included in regular, free bowel cancer screening programs so timely diagnosis is dependent on those people seeking help for symptoms —but that is only part of the story, says Dr. Lamprell.

Patient stories

Dr. Lamprell and her colleagues explored 273 different self-reported patient stories about their diagnoses, and their perceptions of heath service factors that delay diagnosis, via bowel cancer support group websites in the UK, Australia and New Zealand.

“Overwhelmingly, people who experienced delayed diagnoses expressed frustration and a sense of not being heard, or reported disagreement with their doctors over symptom seriousness,” says Dr. Lamprell.

“Most of these patient stories contained a plea, to other patients, health systems and doctors, to understand what they had gone through to get a diagnosis—and more than half also gave advice to other people about how important it is to self-advocate, by clearly communicating concerns, asking for cancer screening, seeking second opinions and being involved decision-making.”

Dr. Lamprell points out that patients may not have grasped the systematic processes that GPs need to go through to provide the best care—”which includes not jumping to a diagnosis of cancer straight away, there’s a number of other investigations to rule out far more common explanations, which have to occur first.”

This approach is especially relevant when patients present with broad symptoms such as abdominal pain and nausea, fluctuating bowel habits, anemia and fatigue, though research is indicating that these may be symptoms of bowel cancer in younger people in early stages of the disease, she says.

However, because younger patients still make up the minority of people with bowel cancer, even when there are red-flag symptoms such as blood in stools, or rectal bleeding, other conditions are more likely to be explored, she says.

“Patients experiencing blood in their poo who were otherwise healthy reported being investigated and treated repeatedly for hemorrhoids or gynecological conditions,” she says.

Time constraints in consultations, and a lack of understanding around doctors’ obligations to provide value-based care potentially contributed to patients’ negative experiences, Dr. Lamprell says.

“Young people who experienced delays in diagnostic pathways due to doctors’ ongoing low suspicion of cancer perceived an age bias impacted diagnostic decision-making.”

“Shared decision-making and clear communication about the reasons for diagnostic decisions may have resolved some of the frustrations expressed by patients who felt that they were not being heard by their doctors,” says Dr. Lamprell.

Positive diagnostic experiences

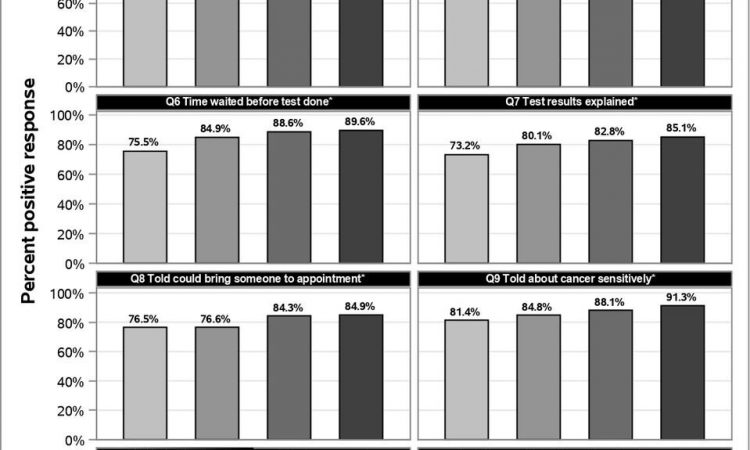

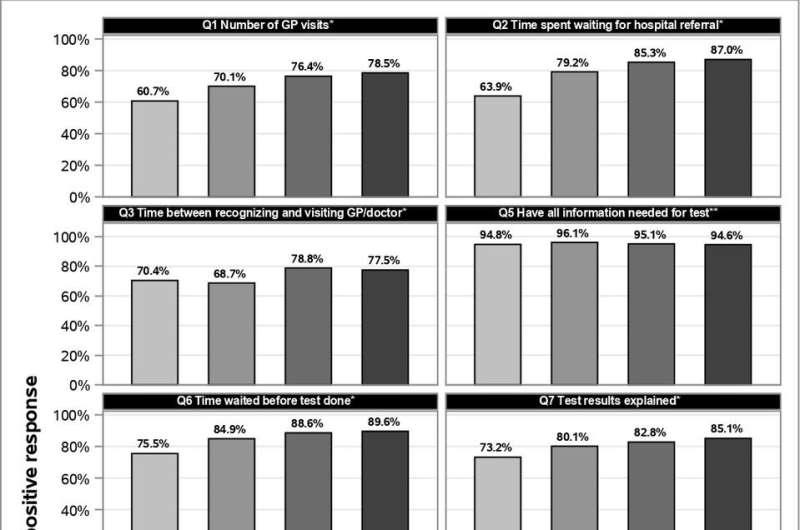

In a complementary study, the researchers also analyzed the experiences of 3889 people in the English National Cancer Patient Experience Survey and found that older patients were 10 to 15 percent more likely to report positive experiences than people aged under 55, suggesting there is likely room to improve the experiences of younger patients.

Dr. Gaston Arnolda, an epidemiologist and Senior Research Fellow at Macquarie University who co-authored the research, said that more recent clinical guidelines, such as the revised Australian clinical practice guidelines in 2018, have provided much clearer guidance on management of younger patients.

“While bowel cancer is still very rare in younger patients, one in ten new bowel cancer cases are now occurring in people under age 50, and this proportion is steadily increasingly.”

Dr. Arnolda adds that because older people make up the majority of bowel cancer patients, communication and information packages may be less likely to address the concerns of a younger group, such as how treatment might impact fertility.

Call for screening

With health authorities worldwide seeing a rise in early-onset bowel cancer, Dr. Arnolda says that there are conversations underway around increasing population-wide screening to occur from age 45. This reduction in age threshold has been recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force, and has been found to be cost-effective in Australia, but is not currently underway.

“Up to half of bowel cancer is preventable, with screening a key element of preventive care, so steps are needed to support GPs to improve the screening participation rate of over-50’s,” says Dr. Arnolda.

“With screening not available for under 50’s, GPs also need support to improve the diagnostic experiences of symptomatic patients under 50, for example, by improving the speed of access to colonoscopy for those with red flag symptoms,” he says.

There’s good reason to be concerned about the increase in early-onset bowel cancer and delays in diagnosis, says Dr. Lamprell.

“Younger people are more likely to be diagnosed in later stages of the disease, and when a diagnosis is delayed, there’s more opportunity for cancer to advance or spread, which can affect survival rates,” she says.

“Bowel cancer detected in its early stages has a very high chance of survival, but delayed diagnosis increases the risk of aggressive surgeries and treatments, at a time when younger people are establishing relationships, raising families and building careers,” she says.

“Timely diagnosis is crucial to this fast-growing patient population.”

More information:

Syeda Somyyah Owais et al, Age-related experiences of colorectal cancer diagnosis: a secondary analysis of the English National Cancer Patient Experience Survey, BMJ Open Gastroenterology (2023). DOI: 10.1136/bmjgast-2022-001066

Klay Lamprell et al, People with early-onset colorectal cancer describe primary care barriers to timely diagnosis: a mixed-methods study of web-based patient reports in the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand, BMC Primary Care (2023). DOI: 10.1186/s12875-023-01967-0

Journal information:

BMJ Open

Source: Read Full Article