Thought LeadersProfessor Diego CuadrosDirector, Health Geography and Disease ModelingUniversity of Cincinnati

Thought LeadersProfessor Diego CuadrosDirector, Health Geography and Disease ModelingUniversity of CincinnatiDespite millions of people living with HIV in Africa, not everyone has access to adequate healthcare. In this interview, we speak to Professor Diego Cuadros who recently mapped access to HIV care in Africa.

Please could you introduce yourself and tell us what inspired your latest research into HIV care?

My name is Diego Cuadros and I am an Assistant Professor of Health Geography, and the director of the Health Geography and Disease Modeling Laboratory at the University of Cincinnati, U.S. I hold a bachelor’s degree in biology from the National University of Colombia, and a Ph.D. in Biology from the University of Kentucky.

My research focuses on spatial epidemiology and mathematical modeling of chronic and infectious diseases, with a particular focus on the HIV epidemic in Africa, but I also study other diseases like malaria, leishmaniasis, tuberculosis, diabetes, and COVID-19.

I started working on the HIV epidemic in Africa during my Ph.D. For my Ph.D. dissertation research, I was interested in understanding the epidemiological implications of co-infections in individuals living with HIV in Africa and estimating the population-level impact of co-infections with parasitic diseases like malaria. After completing my Ph.D. in 2012 I moved to Qatar for my postdoctoral stance at the Weill Cornel Medicine in Qatar.

During that time, I started becoming interested in the application of spatial statistics methods and geospatial techniques to understand the spatial structure of diseases, and to identify the spatial drivers of the geographical distribution of a disease.

In 2015 I moved to South Africa to continue working on implementing geospatial methods to better understand the HIV epidemic in Africa. Then, I joined the University of Cincinnati in 2016 and continued using disease mapping and geospatial techniques to Identify vulnerable populations at high risk of the disease, and also to map vulnerable underserved populations that are lacking adequate health care.

Substantial progress has been done to tackle the HIV epidemic in Africa, particularly thanks to the implementation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) boosted by the ambitious global 90-90-90 strategy. However, the success of such ambitious plans strongly depends on that no one is left behind. Therefore, the inclusion of hard-to-reach populations living in remote rural areas characterized by poor access to adequate treatment and care on these targets becomes a key approach for the success of the global strategy.

In our lab, we recognize the usefulness of geospatial methods for identifying and localizing these hard-to-reach vulnerable populations. Such information becomes a key element for the development and implementation of strategic programs that include these underserved populations.

Image Credit: Maxim Ermolenko/Shutterstock.com

Despite many efforts to increase the number of individuals diagnosed with HIV in Africa who are receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART), many people are still not receiving this. Why is this?

HIV prevalence and incidence are extremely high in the Africa region despite a lot of efforts focused on Africa for several decades. Still, a large number of people living with HIV (PLHV) in Africa are lacking adequate treatment and care, particularly access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) due to limited health-related resources, such as financial/economic funding, national infrastructure to access to health with transportation, and even human resources.

Despite substantial efforts from international organizations and donors, resources to confront the epidemic are limited, and thus strategic spending is needed. Allocative efficiency spending has been shown to be successful strategies taking into account budget constraints and maximizing benefits in terms of reducing HIV incidence and mortality. However, more efforts are needed to identify and target vulnerable populations in need of care. These underserved populations can be located in areas suffering a high burden of the disease in pockets of transmission that are key targets for the control of the epidemic.

We think most people with PLHIV live in urban areas or near urban areas, and most of the healthcare facilities in Africa are concentrated in those areas. But according to our results, about 8 million people with HIV live in rural areas and for the most part, movement is very difficult.

As a result, these hard-to-reach populations living in rural communities with poor access to care might not be receiving adequate ART coverage, in which enrolment but also retainment to treatment is compromised by several barriers including easy access to care products and long-distance to access care.

In your latest research, you discovered that in sub-Saharan Africa 7 million people with HIV live more than 10 minutes away from health care services, and 1.5 million live more than 60 minutes away from a healthcare facility. How did you carry out this research and why are these findings so important?

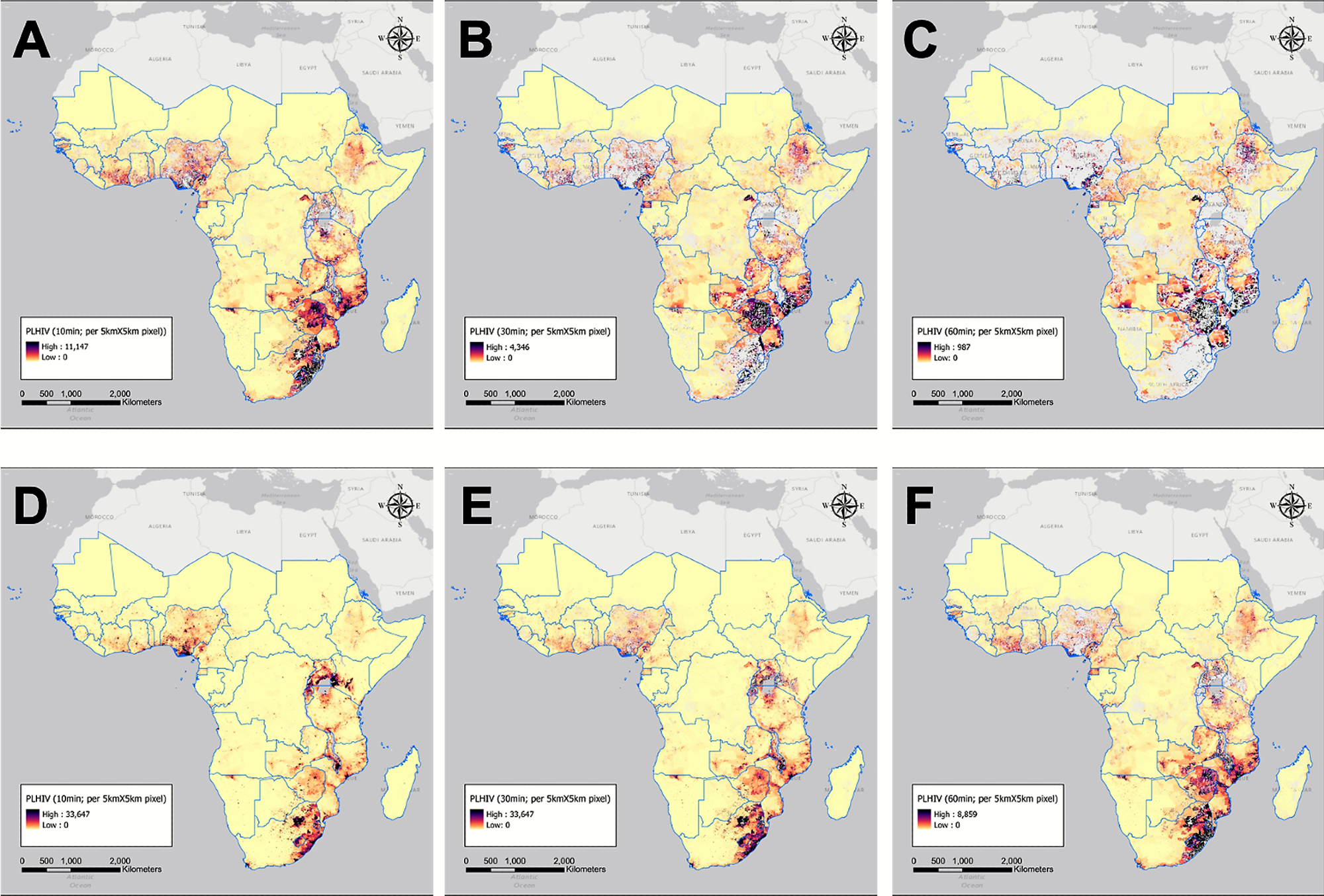

In this study using different geospatial methods, we analyzed data previously generated for the spatial distribution of PLHIV for the entire continent along with data about the minimum travel time needed to reach the nearest facility using motorized or non-motorized vehicles.

For the travel time, the speed of human movement is assumed as the motorized movement along roadways, railways, and on water. Using this information, we geolocated and mapped the PLHV located more than 10, 30, and 60 minutes from the nearest health care facility in Africa. We then calculated the density of PLHV in these travel time zones from the nearest health care facility. These underserved zones were mapped to illustrate the location of underserved communities where health care services cannot be accessed within appropriate travel time.

The identification of these underserved vulnerable populations becomes a key factor to meet global ART coverage targets. Strategic programs can include this information for the development and implementation of interventions targeting these underserved vulnerable communities.

Moreover, although our results illustrate the accessibility from health care for PLHIV, these maps also capture the state of the health care system in general and the access to care for HIV services but also for other diseases including COVID-19.

Our maps are based on accessibility to the nearest health care facility, thus the underserved areas identified for PLHIV can also be linked to underserved areas for the entire community in general. Some distance-related restrictions in African regions affect not only PLHIV but also the entire community facing barriers to adequate access to care within these underserved communities, such as women, elder people/ children, or disabilities. Thus, our maps could represent the significance of accessibility to the general community as much as for PLHIV.

Image Credit: Kim et al., 2021, PLOS ONE

What impact do these statistics have on not only the person suffering from HIV in getting access to quality care but also on healthcare facilities?

Disease maps like the ones presented in our study are powerful tools for the identification of vulnerable communities lacking adequate access to care. These maps identify areas where underserved communities potentially experiencing micorepidemics reside.

In order to meet global UNAIDS targets, the identification and prioritization of these underserved rural communities become a key to reaching the goal of epidemic control. The identified underserved areas are indicators of the challenge faced by PLHIV in accessing health services in SSA, a situation that is likely worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our analyses provide geospatial insights towards the global target for 2025 by examining whether the current allocation of health facilities is sufficiently accessible to PLHIV in SSA, and how many PLHIV are underserved due to spatial heterogeneities of health care services.

What more needs to be done by policymakers and Governments in ensuring more people have access to ART in Africa? What impacts would this have?

One of the first key steps is to identify the communities that are lacking adequate access to care. The maps developed in our study can generate valuable information for the location of these areas where the communities with the highest needs are located and where resources need to be allocated to enhance access to care for these vulnerable communities. However, accessibility in rural areas is a challenging issue in many African countries.

The geography is very difficult, and the infrastructure is deficient. Two of the intuitive solutions could be improving the road system or expanding public transit to improve access to health. Many African countries have attempted these ways to improve their health accessibility in rural areas with financial support from international organizations and the Global Found. However, Africa’s geographical character could be a physical barrier in some Africa rural areas.

Some villages have a few people within a large area so that constructing infrastructure is a financial burden to the government. In order to overcome this issue, decentralization and task shifting have been promoted as essential components of health care scale-up. The decentralization strategy by for example mobile health care units is suggested to reduce the travel time to healthcare by expanding patients’ choice from physicians in hospitals to lower-level professionals in primary health care facilities.

Thus, people who are challenged to access hospitals for treatment due to a limited number of hospitals within their threshold distance could access health care with shortened travel distance. This strategy has already worked in some countries in Africa, such as Malawi and South Africa, by increasing the percentages of attending hospitals for care and shortening the average travel distance to the hospital since the strategy started.

Are there any other alternatives that could be implemented to improve access to healthcare?

The limited infrastructure in several settings in Africa generates an important challenge for adequate access to health care, particularly in remote rural areas. Our study showed that even these remote rural communities are suffering a substantial burden of the disease and many PLHIV in need of care reside in these remote rural areas.

Enhancing access to care would be essential not only for including these hard-to-reach populations into ART programs but also for treating and controlling other chronic diseases associated with HIV. To cover geographically marginalized populations with clinical care, innovative targeting of health care services is required, including decentralization of HIV care.

African countries are facing a considerable shortage of hospitals and health workers, with more than 60% of countries having extreme shortages. To overcome this challenge, although most studies for HIV intervention have focused on hospitals, decentralization and task shifting have been promoted as essential components of HIV treatment and care scale-up.

The decentralization strategy seeks to reduce the travel distance of patients for improving access to care and retention in care, by expanding patients’ choice from physicians in hospitals to lower-level professionals in primary health care facilities for their ART initiation and HIV management and treatment. Thus, decentralization promotes health care accessibility of patients living in regions with a limited number of hospitals, which is beneficial to people in low socioeconomic strata, and health care mobile units could be a useful strategy aimed to provide care to these remote rural communities.

Image Credit: Adam Jan Figel/Shutterstock.com

Do you hope that with continued awareness of unequal access to healthcare, more will be done to help people living in underserved rural communities?

As the World Health Organization and UNAIDS emphasize the importance of treatment and care for all PLHIV, geospatial estimates of the location of underserved areas and PLHIV provide important information about the number of people who are lacking adequate health services. The presence of large underserved areas is a potential indicator of the heterogeneous distribution of the health care resources in a country.

Furthermore, largely underserved areas with high densities of PLHIV indicate not only longer travel times but also an insufficient number of hospitals and health care facilities. Our study has noted the role of underserved areas as a potential source of HIV transmission, which suggests that targeted strategies to underserved areas could reduce not only the incidence of HIV but also other infectious diseases, such as COVID-19.

These findings can contribute to developing cost-effective policies for interventions aimed at underserved areas. Further attention should be given to the development and implementation of tailored intervention programs in areas identified as underserved for PLHIV.

What are the next steps in your research into HIV and healthcare access?

Access to the nearest health care facility is one of the most important measures for HIV treatment success but expanding health care in underserved communities could improve not just HIV response but the response to the COVID-19 pandemic and other public health issues as well. However, the massive global health crisis of COVID-19 has presented enormous challenges for the adequate access to health care for PLHIV including regular health care services along with the disruption of many of the mobile strategies over the past two years.

Unquestionably, the pandemic has substantially disrupted HIV services and care. As a result, it is expected that health outcomes linked to HIV have worsened during this past year in Africa. It would be very important to evaluate these impacts and assess alternative strategies aimed to alleviate these health disruptions, particularly in the underserved communities identified in our study.

Where can readers find more information?

- Weiss D, Nelson A, Vargas-Ruiz C, Gligorić K, Bavadekar S, Gabrilovich E, et al. Global maps of travel time to healthcare facilities. Nature Medicine. 2020:1–4.

- Ouma PO, Maina J, Thuranira PN, Macharia PM, Alegana VA, English M, et al. Access to emergency hospital care provided by the public sector in sub-Saharan Africa in 2015: a geocoded inventory and spatial analysis. The Lancet Global Health. 2018;6(3):e342–e50.

- Hulland E, Wiens K, Shirude S, Morgan J, Bertozzi-Villa A, Farag T, et al. Travel time to health facilities in areas of outbreak potential: maps for guiding local preparedness and response. BMC medicine. 2019;17(1):1–16.

- Dwyer-Lindgren L, Cork MA, Sligar A, Steuben KM, Wilson KF, Provost NR, et al. Mapping HIV prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa between 2000 and 2017. Nature. 2019;570(7760):189–93

- Kim, H., Tanser, F., Tomita, A., Vandormael, A., & Cuadros, D. F. (2021). Beyond HIV prevalence: identifying people living with HIV within underserved areas in South Africa. BMJ global health, 6(4), e004089.

- Cuadros, D. F., Li, J., Branscum, A. J., Akullian, A., Jia, P., Mziray, E. N., & Tanser, F. (2017). Mapping the spatial variability of HIV infection in Sub-Saharan Africa: Effective information for localized HIV prevention and control. Scientific reports, 7(1), 1-11.

About Professor Diego Cuadros

I am an Assistant Professor of Health Geography and the director of the Health Geography and Disease Modeling lab at the University of Cincinnati. My research interest focuses on exploring the variation in HIV infectious spread generated by geospatial cofactors, and how this variation would help us to better understand the natural history of HIV and epidemic typology with emphasis on sub-Saharan Africa.

My research is conducted through mathematical and statistical analyses focusing on measuring the effect of on the HIV epidemic of population-level variations generated by the structure heterogeneous distributions of risk factors.

Posted in: Thought Leaders | Medical Science News | Medical Research News | Disease/Infection News | Healthcare News

Tags: Antiretroviral, Children, Chronic, Diabetes, Disease Modeling, Epidemiology, Global Health, Health Care, Healthcare, HIV, Hospital, Infectious Diseases, Laboratory, Leishmaniasis, Malaria, Medicine, Mortality, Pandemic, pH, Public Health, Research, Tuberculosis, UNAIDS

.png)

Written by

Emily Henderson

During her time at AZoNetwork, Emily has interviewed over 200 leading experts in all areas of science and healthcare including the World Health Organization and the United Nations. She loves being at the forefront of exciting new research and sharing science stories with thought leaders all over the world.

Source: Read Full Article