Infections spread in hospitals and other healthcare settings cause over 680,000 infections and 72,000 patient deaths in the U.S. every year. Surveillance and reporting of these infections to government entities has become a key part of hospital infection control programs, yet infection control experts question the effectiveness of these measures at protecting public health.

That is the finding of a new survey led by researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. Results were recently published in the journal JAMA Network Open.

The UMSOM researchers analyzed results from survey respondents from 43 U.S. hospitals that are part of the Healthcare Epidemiology Research Network, a consortium focusing on research in infection control and antibiotic misuse.

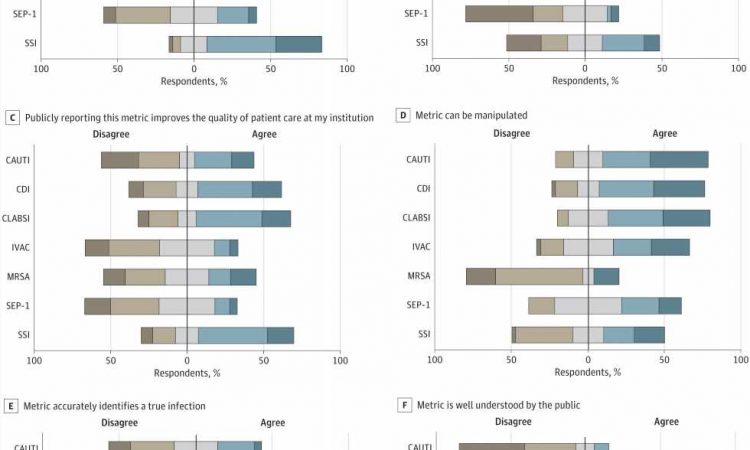

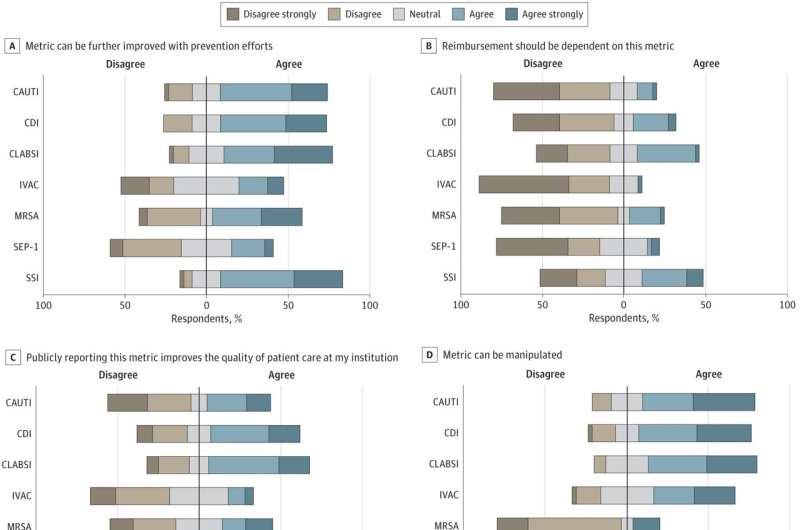

The respondents reported that many metrics, such as surgical site infections and antibiotic-resistant (MRSA) bloodstream infections, were important measures of infection control that should be reported to the federal government. The vast majority of respondents, however, said that two metrics—related to sepsis management and ventilator-associated infections—were not useful measures of infection control efforts.

“These infection control metrics are intended to reflect the quality of care at each institution, but some of the metrics don’t take into account the complex care provided by academic institutions as compared to community hospitals,” said study lead author Gregory Schrank, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine at UMSOM.

“Some have infections that can’t be prevented, while other metrics we are required to report aren’t indicative of an infection and don’t lead to an improvement in the quality of care that patients receive. Our survey found that tracking these metrics can detract from other important infection prevention work.”

Even more surprising, 84 percent of respondents said they believed hospitals and staff “intentionally manipulate” hospital-associated infection rates publicly reported on the government’s Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Hospital Care Compare website.

The federal government sets reimbursement rates for Medicare and Medicaid patients based on these metrics. The data are also used in hospital rankings published by US News & World Report and others. Survey respondents stated that they feel pressure to find ways to avoid reporting cases.

“We found that survey respondents did not believe the metrics reported on these websites were well understood by the public,” said study co-author Daniel Morgan, MD, Professor of Epidemiology & Public Health at UMSOM. “They also did not think reimbursements should be tied to these metrics, given all the caveats to collecting and reporting them.”

While the study researchers pointed out that reporting of hospital-acquired infections has led broadly to an improvement in care, they concluded that the survey highlighted the need for adjustments to these metrics to create less of an incentive for hospitals to game the system.

“While requirements to collect and report hospital metrics were implemented with the best of intentions, improvements clearly can be made to the system,” said UMSOM Dean, Mark T. Gladwin, MD, who is also Vice President for Medical Affairs, University of Maryland, Baltimore, and the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor. “For example, there is a need for a more robust use of risk adjustment tools in these models to create national benchmarks for hospitals that treat the most complicated cases and sickest patients.”

More information:

Gregory M. Schrank et al, Perceptions of Health Care–Associated Infection Metrics by Infection Control Experts, JAMA Network Open (2023). DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.8952

Journal information:

JAMA Network Open

Source: Read Full Article