Lung cancer is the second most common form of cancer worldwide, leading to around 20% of cancer-related deaths. We know that smoking can cause lung cancer, but it is less known that 15–20% of cases occur in nonsmokers. Many of these are due to a nonhereditary gene mutation that develops later in life, causing a type of lung cancer called EGFR positive (EGFR+). Medical News Today spoke to a survivor of EGFR+ lung cancer, and investigated the latest developments in lung cancer research and treatment.

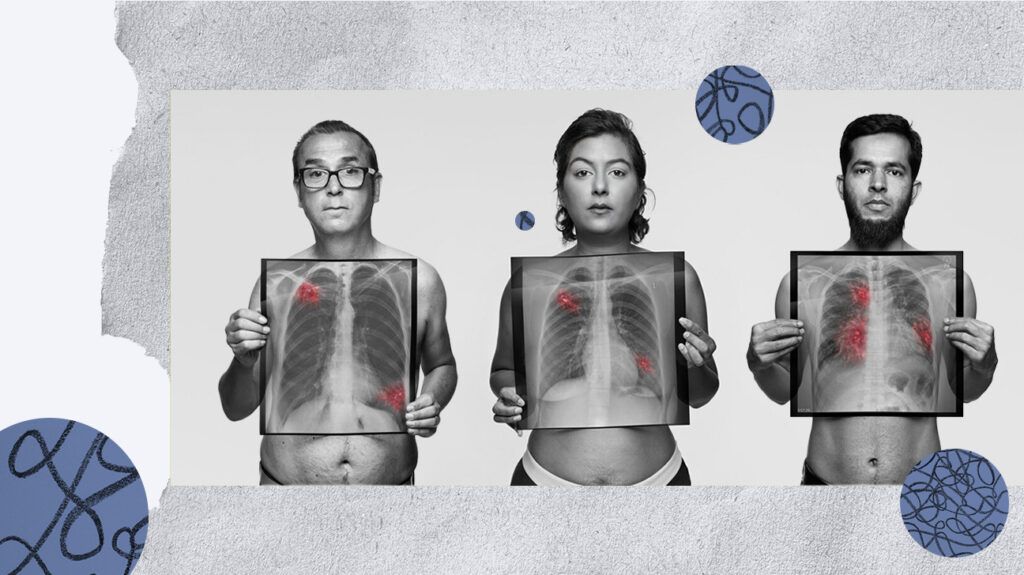

Not everyone who receives a lung cancer diagnosis used to be a smoker. Header design by MNT; photography by Rankin for the See through the symptoms campaign, courtesy of EGFR+ UK.

Smoking tobacco can cause lung cancer — this is an undisputed fact. Cancer Research UK — a United Kingdom nonprofit organization — reports that 72% of lung cancer cases, and 86% of lung cancer deaths, are caused by smoking.

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) state that up to 90% of lung cancer deaths are associated with smoking. Giving up smoking or, better still, never starting to smoke, greatly reduces the risk of lung cancer.

However, not all lung cancer cases can be linked to smoking. And, as the number of smoking-related lung cancers starts to decrease, non-smoking-related lung cancer cases are on the rise.

First, what is lung cancer?

Cancer is a disease in which some of the body’s cells grow uncontrollably and spread to other parts of the body. Lung cancer is any cancer that affects the trachea (windpipe), bronchi (airways), or lung tissue.

The two main types of lung cancer are small cell lung cancer (SCLC), and non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). NSCLC makes up the majority — around 80%–85% — of lung cancers.

NSCLC can be divided into 3 main types:

- adenocarcinoma, which starts in the mucus cells lining the airways

- squamous cell carcinoma, which tends to grow near the centre of the lungs and starts in the flat cells that cover the airway surface

- large cell carcinoma, where cells appear larger than typical cells when examined under a microscope.

Overall, in the U.S., the estimated 5-year survival rate for NSCLC is 28%, meaning that of people with NSCLC, 28% are likely to be alive 5 years after diagnosis. However, survival rates are improving all the time.

Historically, lung cancer has affected more men than women. Smoking peaked among women in the U.S. in the 1960s, so as these women aged, their rates of lung cancer increased. In recent years, there has been a concerning rise in lung cancer in younger women (aged 30-49).

What is EGFR+ lung cancer?

EGFR+ lung cancer is a form of lung cancer, usually an adenocarcinoma, that is not caused by smoking, but by a mutation in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) — a protein involved in the growth and division of healthy cells. The mutation causes the gene to constantly tell cells to divide, leading to malignancies, or cancer.

The American Lung Association (ALA) states that EGFR+ mutation occurs in around 10–15% of lung cancers in the U.S.

The most common EGFR mutations are EGFR 19 deletion — where part of the gene is missing — and EGFR L858R point mutation — where one nucleotide (small unit of DNA) is altered. Less common is the Exon 20 insertion mutation, which causes between 4 and 10% of EGFR+ lung cancer cases.

This type of lung cancer is more common in women than men. It is also more likely to be diagnosed in younger people and people who have never smoked, or who have been light smokers at some stage of their life, than in heavy smokers.

So it could be, in part, responsible for the increases being seen.

Lung cancer in nonsmokers

Many people with lung cancer face harmful stigma about their presumed lifestyles. Collage design by MNT; photography by Rankin for the See through the symptoms campaign, courtesy of EGFR+ UK.

Prof. Robert Rintoul, a professor of thoracic oncology in the Department of Oncology at the University of Cambridge, U.K., and honorary consultant respiratory physician at the Royal Papworth Hospital NHS Foundation Trust in Cambridge, told Medical News Today:

“Because many EGFR+ are never smokers or light smokers, they are not thinking of lung cancer when they develop symptoms. ‘Oh it can’t be anything serious, I have never smoked.’ Therefore often such patients present with more advanced, higher stage disease when they do come to light. Currently around 15% of all the lung cancers we diagnose (regardless of EGFR status) are never smokers — lung cancer is no longer a disease of smokers.”

According to the CDC, up to 20% of lung cancer cases in the U.S. are diagnosed in nonsmokers. Prof. Rintoul advised that everyone, regardless of whether they have ever smoked, should be aware of possible symptoms, which include:

- persistent cough (more than 3 weeks)

- recurrent chest infections

- coughing blood

- losing weight

- unexplained tiredness

- chest pain

- unexplained breathlessness.

However, Dr. Gini Harrison, psychologist and research trustee at EGFR+ UK, and EGFR+ survivor, cautioned that not everyone, particularly with EGFR+ lung cancer, has these typical symptoms.

“I was 40. I had my son in February 2021, and almost immediately, I started getting really bad shoulder pain. That was it. That was my only symptom. No breathing issues, no wheezing, nothing. My GP [primary care practitioner] said it was probably tendonitis due to poor breastfeeding posture,” she told us.

“And,” she added, “many of us only present with musculoskeletal symptoms — such as back, chest or shoulder pain — at diagnosis.”

Partly because of these atypical symptoms, it was 9 months before her cancer was diagnosed.

Does stigma lead to a lack of research?

Lung cancer research suffers from a lack of funding. Although the most common cancer in men and the second most common cancer in women, it receives some of the lowest investment compared to the overall burden of diseaseof any cancer.

It causes 11.4% of cancer cases and 18% of cancer deaths globally, but lung cancer research received only 5.3% of the total investment in cancer research between 2016 and 2020.

Could this be due to the stigma associated to lung cancer? That may be a contributing factor, seeing that around 80-90% of people who die from lung cancer have a history of smoking, and this lifestyle choice is often blamed for the cancer.

But Dr. Harrison is adamant that this viewpoint needs to change:

“We need to raise awareness that lung cancer can happen to anyone with lungs, regardless of smoking status. Breaking this stigma would mean more visibility, more fundraising, more support, more money for research, more knowledge… which ultimately should lead to better and earlier detection of symptoms, better treatments and better survival outcomes.”

Early lung cancer diagnosis is vital

The earlier lung cancer is diagnosed, the better the prognosis. According to the American Cancer Society, those diagnosed when NSCLC is at an early, or localized, stage have a 65% chance of surviving for 5 years.

However, if the cancer has spread to other parts of the body before it is diagnosed, only 9% of those people are likely to live for another 5 years.

Nevertheless, the outlook for those with all types of lung cancer is improving, as Dr. Harrison explained.

“These days, with targeted therapies, people are living way longer than they used to. When you get diagnosed, you Google the statistics and the ones you see are horrendous — that’s terrifying. But those statistics are massively out of date. They haven’t taken into account the targeted therapies,” she pointed out.

Treatment options and targeted therapies for lung cancer

The treatments for NSCLC depend on the stage of the cancer.

A cancer that is detected early may be entirely removed by surgery, photodynamic therapy (PDT), laser therapy, or brachytherapy (internal radiation), without any need for follow-up therapies. The later the cancer is diagnosed, and the further it has spread, the more intensive the therapy that is needed.

Later stages of lung cancer may be treated using surgery followed by radiation therapy, immunotherapy (medications that help the immune system fight the cancer), and/or chemotherapy. The tumors will be tested for gene mutations so that therapy can be targeted.

EGFR+ lung cancer is also treated with a group of drugs called tyrosine kinase inhibitors, or TKIs, which inhibit the enzymes that activate proteins such as EGFR.

There are five approved TKIs for treating EGFR+ lung cancer:

- Tarceva (erlotinib)

- Gilotrif (afatanib)

- Iressa (gefitinib)

- Vizimpro (dacomitinib)

- Tagrisso (osimertinib).

These medications can greatly improve the survival and quality of life of NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations. However, their efficacy can be affected by other gene mutations, and tumors can become resistant to them.

According to EGFR+ UK, how long the drugs are effective varies from patient to patient. If the cancer becomes resistant, it will start to grow or spread, and doctors will then carry out genetic tests to see what mutation has occurred. Often, they will then try a different TKI, which many people will respond well to, chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

For Dr. Harrison, genetic testing showed that her cancer was Exon 20, which does not respond to TKIs. “When I was diagnosed, there were no targeted treatments for Exon 20, so they decided on chemo radiation because it was quite local.”

Having undergone several months of chemo and radiotherapy, she now has no evidence of cancer, although she does have some lasting effects: “What has happened is the top of my lung has collapsed, as a result of the radiation, and my ribs just keep breaking, but it’s not cancer!”

New developments and research breakthroughs

Despite funding shortages, there have been some recent breakthroughs in EGFR+ lung cancer research.

One study earlier in 2023 found that CD70, a gene that promotes cell survival and invasiveness, and has been implicated in the development of other cancers —such as glioblastoma, the most common type of brain tumor — could be a therapeutic target for people with resistant EGFR+ lung cancer.

Another study has suggested that a vaccine may prevent the development of common EGFR mutation-driven lung tumors, by activating immune cells, but this research is in its early stages.

Targeted, combined therapies seem to be the most promising route, as Dr. Elene Mariamidze, from Todua Clinic, in Tbilisi, Georgia, argued at the ESMO Congress 2023:

“We are entering an era of personalised medicine in NSCLC where we are using combinations of novel, targeted agents, and it will be essential to know the whole mutational burden of each patient at diagnosis so we can properly plan the most effective and least toxic approach. The future of lung cancer care lies in finding the right combination of targeted treatment, or chemotherapy with immunotherapy for each patient.”

Marcia K. Horn, juris doctor, president and CEO of the International Cancer Advocacy Network, and executive director of the Exon 20 Group, told MNT that there is new hope for those with the rarer Exon 20 mutation EGFR+ cancer.

“Our patients and care partners who are members of the Exon 20 Group were overjoyed at the PAPILLON clinical trial data announced at Madrid’s recent ESMO Congress,” she said.

“What the PAPILLON data means is that we now have a new first-line therapy for EGFR exon 20 insertion-mutated patients of amivantamab plus the chemo doublet of pemetrexed/ALIMTA plus carboplatin. I cannot overstate the importance of having such a transformative first-line therapy available for our patient population,” she added.

Can lung cancer become a controlled illness?

According to EGFR+ UK, the goal is for EGFR mutant lung cancer to become a chronic, controlled illness that people will be able to live for many years.

However, as Dr. Harrison told MNT, the care a person gets depends on where they live: “There are new breakthroughs happening all of the time, but while there are many clinical trials sited in the U.S…. very few have sites in the U.K., and we have much worse access to drugs over here.”

“Disparity of care is enormous, both within the U.K. and between different countries. It’s horribly frustrating,” she added. “Patient advocacy is so important. Our role in the charity is helping patients navigate and informing them, giving them the power to be advocates for themselves.”

But the outlook is improving. “These days, people are living much longer. I know someone who is alive 34 years after diagnosis,” Dr. Harrison told us.

“The longer I do this, the more people I meet who are living 10 years and beyond. It was less than 1% when I Googled it. I think things are shifting.”

Source: Read Full Article