We’re once again seeing patients in hospital with severe cases of COVID-19, despite being triple vaccinated and not being immunocompromised. Colas Tcherakian, MD, respiratory medicine specialist at the Foch Hospital, Paris, France, presents two recent COVID case studies and explains why this new wave is similar to the first. What lessons can be learned?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Good morning, I’m Colas Tcherakian, a respiratory medicine specialist at Foch Hospital, and I’m going to discuss two cases that reflect what we’re seeing quite often nowadays. I’ve called them “COVID-22 case studies” because it’s 2022 and the virus has changed a lot since the COVID-19 we first heard about. Nowadays, this “COVID-22” reminds us of what we were faced with in 2020, during the first wave of the pandemic. But, in what way? Because this eighth wave has now plateaued and we’re seeing patients that we weren’t seeing before. Once again, we’re seeing seriously ill patients with no apparent comorbidities, who are not immunocompromised and have been vaccinated. We need to look at these patients because I think they can teach us several things.

Patient One: Severe COVID in a Triple-Vaccinated Patient

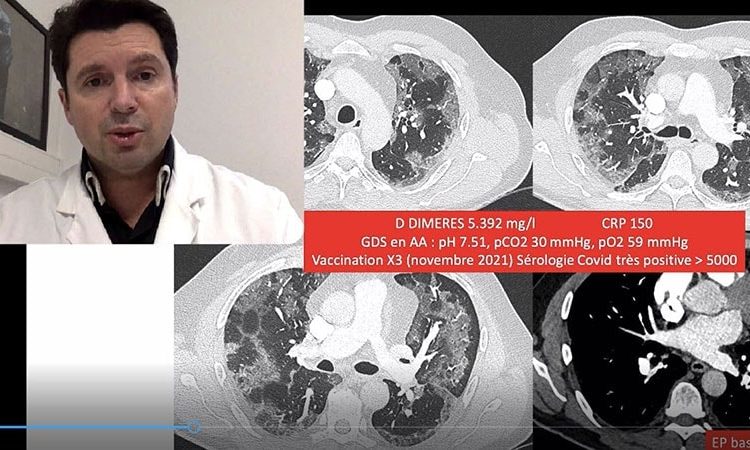

Let’s look at the first patient, a 59-year-old male. He had very little previous history, uncomplicated dyslipidemia, and, what’s more, he was only receiving treatment for this with a lipid-lowering drug. He is a smoker. This is very important, because we know that smoking is still a risk factor for COVID complications. He has smoked 10 cigarettes a day for around 30 years. He started with mild symptoms, with cough, shortness of breath, and a fever. When his fever worsened, the patient used over-the-phone medical services to speak with a doctor who prescribed corticosteroids and Augmentin (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid). Despite starting this treatment, the patient’s condition worsened over the following days. After seeing his family physician, who found the patient’s oxygen saturation to be low, he was referred to the hospital’s emergency department.

In this patient we see features that some of us know very well: a mixture of typical features of COVID with some signs of organizing pneumonia about to appear in a patient with hypoxemia. One important point to note is that his D-dimers were very high, and a small pulmonary embolism was detected. In short, a clinical picture that would have been completely classic in 2020, the only difference being that this patient has received three vaccine doses. The fact that he’d indeed received three vaccine doses is likely to be significant. We know he’s had them because his COVID serology results were very positive at more than 5000 BAU. This means he couldn’t be more protected in terms of antibodies. We’ve talked about this in a previous Medscape video. Namely, that high antibody levels are not a given for protection and, what’s more, I advised against testing antibody levels to determine whether to further vaccinate a patient. This patient is proof of this. There is no good antibody-protection correlation. You can have no antibodies and a good cellular response and not be infected and, like in this patient’s case, have antibody levels through the roof and still develop a severe form of COVID.

However, we weren’t seeing these latter types of patients anymore, so what’s changed? Is it because the patient had his last dose of the vaccine too long ago? We know that, more than the level of antibodies, it’s probably the time from the last dose that is the predictive factor in getting COVID. We had a rule that said, “if you have no comorbidities, are not immunocompromised, and have had three doses, you won’t end up in hospital.” And this was true until the latest wave, the seventh, when we stopped seeing this type of patient.

So, is it because he had his last vaccine dose too long ago (November 2021)? Is this a new variant — BQ.1.1 — with some features like that of the Wuhan virus, with lung tropism and a secondary risk of embolism? This is something to consider. I think how the wave progresses will confirm whether we’re likely to see more patients like this.

Patient Two: COVID With Lung Lesions in a Patient on DOACs

Another case, that of a 69-year-old male patient who, this time, has a more extensive medical history. It includes a history of strokes, the aftereffects of which have been minimal atrial fibrillation. What is very interesting in this patient is that he is being treated with direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) and he is also an active smoker — six to seven cigarettes per day. We must remember smoking is a risk factor, contrary to what was initially reported.

Whilst having COVID, the patient also had a small pulmonary embolism with a second feature — lung lesions. We’ve already described this with the typical form of COVID, where you could just have COVID in the form of a pulmonary embolism with, sometimes, very significant clots and no parenchymal lesions. And so, we would say to ourselves: “be careful, any patients with a pulmonary embolism during the COVID epidemic must be tested for COVID.” Why? Because if you’re positive for COVID, this means it’s a predisposing factor and the patient will only be treated for 3 months. Conversely, if COVID is not detected and the pulmonary embolism cannot be explained, you will start a more long-term treatment plan. So, it’s always worth doing a COVID PCR on a patient with a pulmonary embolism during the COVID epidemic, even if they have no lesions, few symptoms, and no fever.

In this case, once again we had a triple-vaccinated patient with an embolism and signs of inflammation, whose vaccination status was confirmed by positive serology results (590 BAU), which is the level it should be at. So, we have found a slightly different type of patient, but with the same features. COVID can cause embolism, even in patients on DOACs. That’s why [low molecular weight heparin] (LMWH) was initially proposed during the acute phase, because we’ve never had a relapse on a LMWH, unlike with DOACs.

So, we have a second type of patient, with an isolated pulmonary embolism, including those on anticoagulants, and these should be monitored.

Conclusion

The point of this discussion isn’t necessarily to cause alarm, but to say that today we seem to be detecting COVID again as we saw before, and this is probably worth discussing, as well as facilitating vaccination for those patients whose last vaccine dose was over 6 months ago. It also perhaps appears that those with no comorbidities, whom we felt were quite safe, may now be at more risk than before.

So, be alert and stop thinking that current COVID types, and probably BQ.1.1, are just a cold, as we believed at one time for patients who had just been vaccinated, as well as being under the impression that we would no longer see that type of COVID in a hospital setting.

Thank you. I’ll be back to discuss vaccination.

This content was originally published on Medscape French edition.

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

Source: Read Full Article