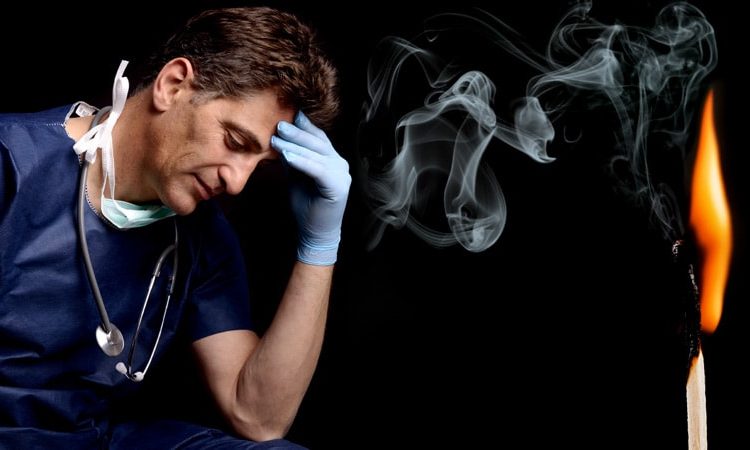

There is a feeling of exhaustion, being unable to shake a lingering cold, suffering from frequent headaches and gastrointestinal disturbances, sleeplessness and shortness of breath…

That was how burnout was described by clinical psychologist Herbert Freudenberger, PhD, who first used the phrase in a paper back in 1974, after observing the emotional depletion and accompanying psychosomatic symptoms among volunteer staff of a free clinic in New York City. He called it “burnout,” a term borrowed from the slang of substance abusers.

It has now been established beyond a shadow of a doubt that burnout is a serious issue facing physicians across specialties, albeit some more intensely than others. But with the constant barrage of stories published on an almost daily basis, along with studies and surveys, it begs the question: Are physicians getting tired of hearing about burnout? In other words, are they getting “burned out” about burnout?

Some have suggested that the focus should be more on tackling burnout and instituting viable solutions rather than rehashing the problem.

There haven’t been studies or surveys on this question, but several experts have offered their opinion.

Jonathan Fisher, MD, a cardiologist and organizational well-being and resiliency leader at Novant Health, Charlotte, North Carolina, cautioned that he hesitates to speak about what physicians in general believe. “We are a diverse group of nearly 1 million in the US alone,” he said.

But he noted that there is a specific phenomenon among burned-out healthcare providers who are “burned out on burnout.” “Essentially, the underlying thought is ‘talk is cheap and we want action,'” said Fisher, who is chair and co-founder of the Ending Physician Burnout Global Summit that was held last year. “This reaction is often a reflection of disheartened physicians’ sense of hopelessness and cynicism that systemic change to improve working conditions will happen in our lifetime.”

Fisher explained that “typically, anyone suffering — physicians or nonphysicians — cares more about ending the suffering as soon as possible than learning its causes, but to alleviate suffering at its core— including the emotional suffering of burnout — we must understand the many causes.”

“To address both the organizational and individual drivers of burnout requires a keen awareness of the thoughts, fears, and dreams of physicians, healthcare executives, and all other stakeholders in healthcare,” he added.

Burnout, of course, is a very real problem. The 2022 Medscape Physician Burnout & Depression Report found that nearly half of all respondents (47%) said they are burned out, which was higher than the prior year. Perhaps not surprisingly, burnout among emergency physicians took the biggest leap, jumping from 43% in 2021 to 60% this year. More than half of critical care physicians (56%) also reported that they were burned out.

The World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) — the official compendium of diseases — has categorized burnout as a “syndrome” that results from “chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed.” It is considered to be an occupational phenomenon and is not classified as a medical condition.

But whether or not physicians are burned out hearing about burnout remains unclear. “I am not sure if physicians are tired of hearing about ‘burnout,’ but I do think that they want to hear about solutions that go beyond just telling them to take better care of themselves,” said Anne Thorndike, MD, MPH, an internal medicine physician at Massachusetts General Hospital and associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “There are major systematic factors that contribute to physicians burning out.”

Why Talk About Negative Outcomes?

Jonathan Ripp, MD, MPH, however, is familiar with this sentiment. “‘Why do we keep identifying a problem without solutions’ is certainly a sentiment that is being expressed,” he said. “It’s a negative outcome, so why do we keep talking about negative outcomes?”

Ripp, who is a professor of medicine, medical education, and geriatrics and palliative medicine; the senior associate dean for well-being and resilience; and chief wellness officer at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, is also a well-known expert and researcher in burnout and physician well-being.

He noted that burnout was one of the first “tools” used as a metric to measure well-being, but it is a negative measurement. “It’s been around a long time and so it has a lot of evidence,” said Ripp. “But that said, there are other ways of measuring well-being without a negative association, and ways of measuring meaning in work — fulfillment and satisfaction, and so on. It should be balanced.”

But for the average physician not familiar with the long legacy of research, they may be frustrated by this situation. “Then they ask, ‘Why are you just showing me more of this instead of doing something about it,’ but we are actually doing something about it,” said Ripp.

There are many efforts underway, he explained, but it’s a challenging and complex issue. “There are numerous drivers impacting the well-being of any given segment within the healthcare workforce,” he said. “It will also vary by discipline and location, and there are also a host of individual factors that may have very little to do with the work environment. There are some very well-established efforts for an organizational approach, but it remains to be seen which is the most effective.”

But in broad strokes, he continued, it’s about tackling the system and not about making an individual more resilient. “Individuals that do engage in activities that improve resilience do better, but that’s not what this is about — it’s not going to solve the problem,” said Ripp. “Those of us like myself, who are working in this space, are trying to promote a culture of well-being — at the system level.”

The question is how to enable the workforce to do their best work in an efficient way so that the balance of their activities are not the meaningless aspects. “And instead, shoot that balance to the meaningful aspects of work,” he added. “There are enormous challenges, but even though we are working on solutions, I can see how the individual may not see that — they may say, ‘Stop telling me to be resilient, stop telling me there’s a problem,’ but we’re working on it.”

Moving Medicine Forward

James Jerzak, MD, a family physician in Green Bay, Wisconsin, and physician lead at Bellin Health, noted that “it seems to me that doctors aren’t burned out talking about burnout, but they are burned out hearing that the solution to burnout is simply for them to become more resilient,” he said. “In actuality, the path to dealing with this huge problem is to make meaningful systemic changes in how medicine is practiced.”

He reiterated that medical care has become increasingly complex, with the aging of the population; the increasing incidence of chronic diseases, such as diabetes; the challenges with the increasing cost of care, higher copays, and lack of health insurance for a large portion of the country; and general incivility toward healthcare workers that was exacerbated by the pandemic.

“This has all led to significantly increased stress levels for medical workers,” he said. “Couple all of that with the increased work involved in meeting the demands of the electronic health record, and it is clear that the current situation is unsustainable.”

In his own healthcare system, moving medicine forward has meant advancing team-based care, which translates to expanding teams to include adequate support for physicians. This strategy addressed problems in healthcare delivery, part of which is burnout.

“In many systems practicing advanced team-based care, the ancillary staff — medical assistants, LPNs, and RNs — play an enhanced role in the patient visit and perform functions such as quality care gap closure, medication review and refill pending, pending orders, and helping with documentation,” he said. “Although the current healthcare workforce shortages has created challenges, there are a lot of innovative approaches being tried [that are] aimed at providing solutions.”

The second key factor is for systems is to develop robust support for their providers with a broad range of team members, such as case managers, clinical pharmacists, diabetic educators, care coordinators, and others. “The day has passed where individual physicians can effectivity manage all of the complexities of care, especially since there are so many nonclinical factors affecting care,” said Jerzak.

“The recent focus on the social determinants of health and health equity underlies the fact that it truly takes a team of healthcare professionals working together to provide optimal care for patients,” he said.

Thorndike, who mentors premedical and medical trainees, has pointed out that burnout begins way before an individual enters the workplace as a doctor. Burnout begins in the earliest stages of medical practice, with the application process to medical school. The admissions process extends over a 12-month period, causing a great deal of “toxic stress.”

One study found that compared with non-premedical students, premedical students had greater depression severity and emotional exhaustion.

“The current system of medical school admissions ignores the toll that the lengthy and emotionally exhausting process takes on aspiring physicians,” she said. “This is just one example of many in training and healthcare that requires physicians to set aside their own lives to achieve their goals and to provide the best possible care to others.”

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Source: Read Full Article