‘Give us the chance to try experimental treatments to beat rare cancer type which killed Bowelbabe Dame Deborah James’

- One in ten bowel cancer patients has a gene mutation affecting people under 50

- Dame Deborah James, 40, who died last year, was among those with the strain

Young people with the same rare bowel cancer that hit Dame Deborah James are calling on health chiefs to allow them to take experimental treatments that might give them precious extra time.

Bowel cancer affects more than 42,000 Britons each year and sufferers are typically over 50, but one in ten have a type caused by the BRAF V600E genetic mutation which often affects younger people.

This form of the disease is incurable and often aggressive, and standard chemotherapy and other medications, used to slow the spread of tumours, quickly become ineffective. The average survival is 12 months.

Dame Deborah was diagnosed with BRAF V600E bowel cancer in 2016, and built up a massive social media following, under the name Bowelbabe, while documenting her progress and raising awareness of the disease and its symptoms until her death last year.

Currently there are at least ten clinical trials into new drug treatments for BRAF V600E bowel cancer but the majority of them are being conducted in the US. Just one of these is open to UK patients.

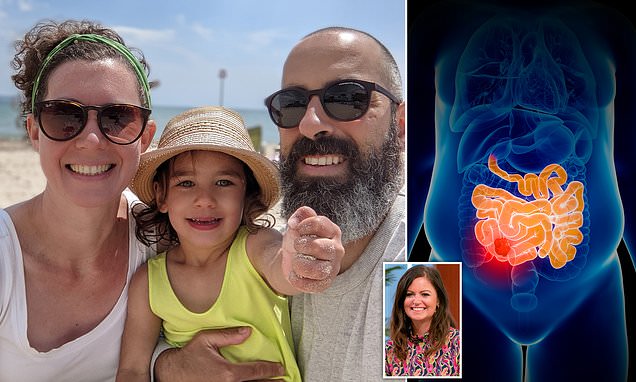

‘DISAPPOINTING’: Clare Mariconda, 40, who was diagnosed in December 2020, hopes a trial would give her more time with her four-year-old daughter, Bethan, and husband, Antonio

Dame Deborah James, 40, was diagnosed with BRAF V600E bowel cancer in 2016, and built up a massive social media following, raising awareness of the disease until her death last year

Patient group Breaking BRAF say that it’s a ‘terrifying’ situation, and have issued an urgent plea to policymakers to fund clinical trials that could offer some hope.

What’s the difference… between visceral and subcutaneous fat?

Visceral fat is a type that is mostly hidden. It is stored inside the abdomen and wraps around the organs, including the liver and kidneys.

Too much of it raises the risk of developing serious illnesses, including Alzheimer’s, heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

Waist size can be an indicator of having too much visceral fat. Women are considered at high risk of chronic disease if theirs is more than 31.5 in (80 cm), or 37 in (94 cm) for men.

Subcutaneous fat is stored in the deepest layer of the skin and is the most plentiful in the body. It mainly collects around the hips, buttocks, thighs and belly, and is considered less harmful than visceral fat.

It helps to store energy and protects bones from falls. It also insulates the body, which helps to regulate temperature.

‘There is a significant amount of research being carried out globally, but very little is in the UK,’ a spokesman said. ‘Patients are missing out on potentially transformative therapies. Time is running out for young families who have the devastating BRAF mutation.’

BOWEL cancer specialist Dr Andy Gaya, at The London Clinic, said the situation was ‘very frustrating’, adding: ‘This is a group of patients with an aggressive cancer and a large unmet need. I would love to see funding and resources ring-fenced to allow us to carry out clinical trials into treatments.’

Last year there was excitement when US doctors announced that a trial of BRAF V600E patients given encorafenib and cetuximab – already standard treatments available on the NHS – plus a type of immunotherapy called nivolumab, survived for an average of 15 months compared with nine months on standard drugs alone.

Half of the patients responded to the triple-drug combo, compared with just one in five of those given only encorafenib and cetuximab.

Dr Gaya said the trial was ‘tantalising’, but added: ‘It was just 23 patients and these early-phase trials only ever include the healthiest, who are most likely to be able to withstand any side effects so we need to be cautious about interpreting the results. A bigger trial is being done, but unfortunately it’s not in the UK.’

Although any doctor can apply to offer medication as part of a trial, the process is complex and requires extra staff to monitor patients.

For this reason, NHS Trusts carry out few of these studies. Cancer Research UK runs clinical trials units but closed two – one in Scotland and one in Wales – earlier this year, leaving just six to cover the UK. The charity has devoted resources to early-stage lab research, but this does not usually involve patients.

All clinical trials were halted during the Covid pandemic and experts admit there are problems getting them back up and running.

Bowel cancer affects more than 42,000 Britons each year and sufferers are typically over 50, but one in ten have a type caused by the BRAF V600E genetic mutation which often affects younger people

Dr Gaya said that reducing the NHS waiting lists and backlogs had taken precedence over research: ‘Running a trial takes a lot of extra time and resources, and since the pandemic many of my colleagues are just trying to keep their heads above water.’

READ MORE: FAREWELL DAME DEBORAH, AS LORRAINE KELLY JOINS MOURNERS AT FUNERAL SERVICE

The immunotherapy drug which proved successful in the US trial, nivolumab, works by helping the immune system to recognise and attack tumour cells. It is offered on the NHS for melanoma skin cancer, kidney and lung cancers, as well as some other more rare genetic types of bowel cancer.

Professor Marco Gerlinger, Head of Gastrointestinal Cancer Medicine at Barts Cancer Institute, said: ‘Whether it is going to work for BRAF V600E bowel cancers isn’t clear yet. Clinical trials will tell us if the benefits justify the risks.’

Immunotherapy side effects can include immune system reactions, liver problems, joint and muscle pain and blistering skin. But some BRAF V600E patients say they are willing to take the chance.

Clare Mariconda, 40, who was diagnosed in December 2020, is one of them.

‘I was on chemo for 12 months but the cancer spread to my liver, so I switched to encorafenib and cetuximab,’ says Clare, who lives in Cambridge with husband Antonio, 41, and daughter Bethan, four.

‘It controlled the cancer for six months, but then tumours started to appear in my bones – my spine, collarbone and knee.

‘A year ago I was put back on chemo, but when this stops working it’s unclear what’s next.

‘I try to keep in the moment and appreciate what I have, but it’s a challenge.

‘We hear about trials in America but not here – it’s disappointing. I know I won’t be cured, but I have a daughter who’s nearly five. I just want to kick the can down the road for as long as I can.’

Source: Read Full Article