Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurological and developmental condition that affects how humans communicate, learn new things and behave. Symptoms of ASD can include difficulties in interacting with others and adapting to changes in routine, repetitive behaviors, irritability and restricted or fixated interests for specific things.

While symptoms of autism can emerge at any age, the first signs generally start to show within the first two years of a child’s life. People with ASD can encounter numerous challenges, which can be addressed through support services, talk therapy and sometimes medication.

To this day, neuroscientists and medical researchers have not identified the primary causes of ASD. Nonetheless, past findings suggest that it could be caused by the interaction of specific genes with environmental factors.

Interestingly, recent neuroscience studies have found that the biological makeup of the gut could contribute to some of the most characteristic symptoms of ASD. More specifically, experiments on mice suggest that the pathway between gut bacteria and the central nervous system can affect social behaviors.

Building on previous findings, researchers at University of Rome ‘Tor Vergata’ and University of Calabria have recently carried out a new study on mice, investigating the effects of transplanting fecal microbiota gathered from autistic donors to mice. Their results, published in Neuroscience, provide further evidence that links gut microbiota with social behaviors typical of ASD.

“Fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) via gavage from autistic children donors to mice, led to the colonization of ASD-like microbiota and autistic behaviors compared to the offspring of pregnant females exposed to valproic acid (VPA),” Ennio Avolio and his colleagues wrote in their paper. “Such variations seemed to be tightly associated with increased populations of Tenericutes plus a notable reduction (p < 0.001) of Actinobacteria and Candidatus S. in the gastrointestinal region of FMT mice as compared to controls."

Essentially, Avolio and his colleagues examined two different groups of mice. Mice in the first group (i.e., the experimental group) received transplanted microbiota originating from the gut of children with ASD, while mice in the other (i.e., the control group) were exposed to VPA, a synthetic compound with anticonvulsant properties, while in their mothers’ wounds.

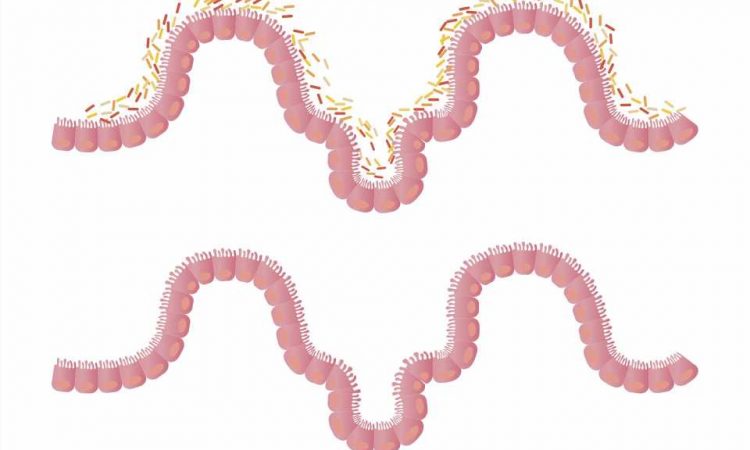

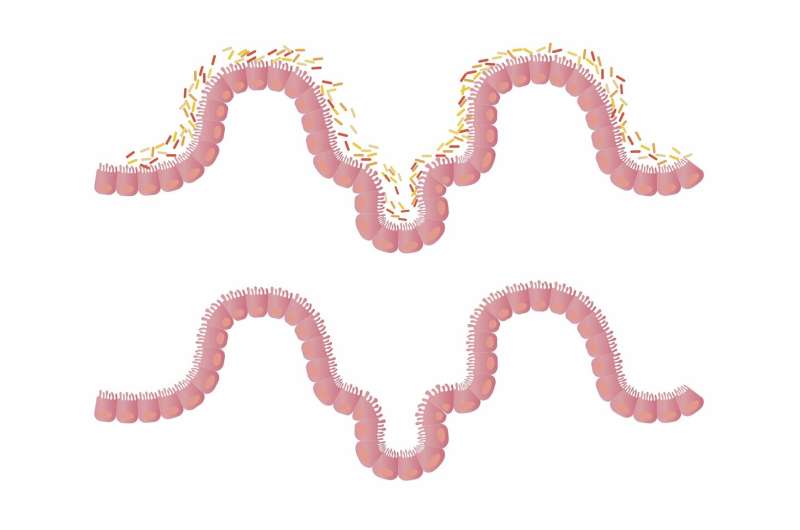

“Contextually, FMT accounted for elevated expression levels of the pro-inflammatory factors IL-1β, IL-6, COX-1 and TNF-α in both brain and small intestine,” the researchers wrote in their paper. “Villous atrophy and inflammatory infiltration (Caspase 3 and Ki67) were increased in the small intestine of FMT and VPA mice compared to controls. Moreover, the observed FMT-dependent alterations were linked to a decrease in the methylation status.”

Interestingly, Avolio and his colleagues observed that the mice who received the ASD microbiota exhibited unusual behaviors while completing different maze tests that are widely used in neuroscience studies. Their behaviors could be linked to those observed in children and adults with ASD.

The recent findings gathered by this team of researchers seem to confirm previous results in the field, suggesting that gut microbiota can indeed play a role in social behaviors. In the future, they could inspire new research in this area and contribute to the testing and gradual introduction of treatments for autism that also consider diet and gut health.

Source: Read Full Article