Distinguishing myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) from acute myeloid leukemia (AML) solely on the basis of a 20% bone marrow blast cutoff ignores important patient characteristics and genetic factors that should be shaping diagnostic and treatment decisions, experts argue in an editorial published in Cancer.

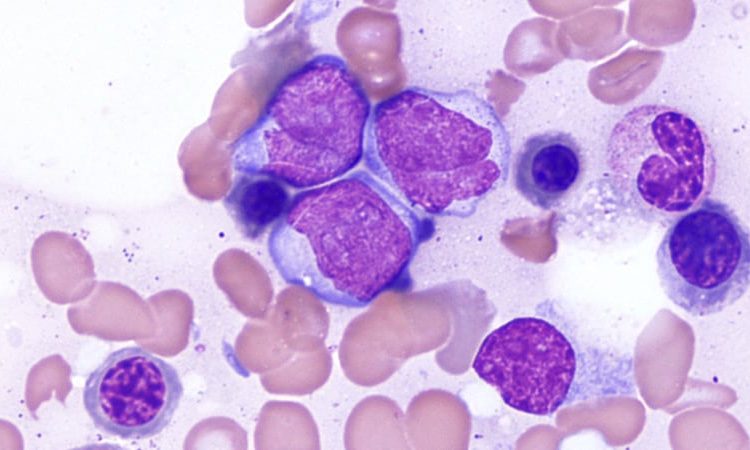

Bone marrow blast rate is commonly used to differentiate MDS from AML — with rates below 20% signaling MDS and those above 20% indicating AML. But a growing body of evidence shows that characteristics, including age and fitness, as well as cytogenetic and mutational profiles are more relevant.

Accurately diagnosing these conditions has become “particularly relevant as available treatments for patients with MDS and AML continue to expand, with often markedly different regimens recommended to a patient according to the semantics of the MDS definition versus the AML definition,” Courtney DiNardo, MD, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and colleagues write.

In the editorial published online February 8, DiNardo and colleagues make their case.

One challenge, they note, “is the lack of accuracy and reproducibility in the initial morphologic blast assessment.” In a 2011 analysis, for instance, researchers at MD Anderson identified a blast percentage discrepancy between diagnoses made at referral and tertiary care centers among 915 patients initially diagnosed with MDS.

Other studies point to the importance of incorporating factors other than blast rate when differentiating between MDS and AML. In one analysis, DiNardo and colleagues found that patients diagnosed with AML and 20% to 29% blasts had more clinicopathologic features in common with patients diagnosed with MDS compared to those with AML and 30% or more blasts. The common features included older age, lower white blood cell counts, and a lower frequency of NPM1 and FLT3-ITD mutations as well as similar median overall survival: 16 months for both MDS with 10% to 19% blasts and AML with 20% to 29% blasts vs 13.5 months for AML with ≥30% blasts.

In addition, among patients aged 60 and younger, AML-type intensive chemotherapy resulted in similar outcomes regardless of blast percentage, suggesting that intensive chemotherapy may be the optimal treatment choice for younger patients with 10% or more blasts, the editorialists note.

“It is of significant importance that the bone marrow blast percentage at diagnosis was not an independent factor for survival in the multivariate analysis of this patient population,” DiNardo and colleagues write.

A 2019 study, also from the editorialists, highlighted the value of using intensive chemotherapy over hypomethylating agents as frontline treatment for younger patients with MDS and 10% or more blasts. Those who received frontline intensive chemotherapy had a significantly higher complete remission rate (63% vs 30%; P < .001) and longer median overall survival (43 vs 15 months; P = .05) compared to those treated with hypomethylating agents.

This analysis “corroborated the effectiveness of [intensive chemotherapy] over [hypomethylating agents] as a frontline treatment for younger patients with excess blasts,” the editorialists write.

In terms of genetic features, a recent study categorized patients with MDS by genomic groups and found that those with “AML-like mutations” in NPM1, FLT3, DNMT3A, RUNX1, and IDH1 frequently had excess blasts and demonstrated a high risk of leukemic transformation.

“Genomic analyses further substantiate the knowledge that molecularly defined signatures or functional pathways can better discriminate biologically and clinically similar myeloid disease, regardless of the bone marrow blast count,” the editorialists write.

Robert Hasserjian, MD, professor of pathology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, agrees that clinicians place too much importance on the bone marrow blast percentage when making treatment decisions.

As Hasserjian previously reported, AML with 20% to 29% blasts (so-called oligoblastic AML) is less aggressive than AML with higher blast counts, and those with oligoblastic AML also share mutation profiles and other features that align more closely with those observed in MDS patients with excess blasts.

“These data suggest that ‘oligoblastic AML’ may represent an intermediate diagnostic category between MDS and AML and challenge the notion that the 20% cutoff separates two distinct diseases,” he said.

Hasserjian also noted that certain genetic mutations, such as NPM1, should be considered AML-defining features and indicate the need for more intensive therapy.

However, he added, “I don’t think we yet have fully mature evidence to know what combination of disease-related parameters — blast count, cytogenetics, mutation profile — and patient-related parameters — age and performance status — should determine optimal therapy.”

Ideally, Hasserjian would like to see more clinical trials to help refine the criteria for differentiating between AML and MDS and in deciding on an optimal therapy. But that won’t be possible if clinical trials continue to segregate patients based on a 20% blast count.

“I think an important step in moving towards a more ‘holistic’ approach to defining MDS vs AML and refining treatment approaches is to devise more clinical trials that use mutations and cytogenetics categories rather than blast percentage cutoffs as inclusion criteria,” he suggested.

DiNardo reports having received research grants from AbbVie, Agios/Servier, Astex, Calithera, Celgene/BMS, Cleave, Daiichi-Sankyo, Immune-Onc, and Loxo as well as honoraria from AbbVie, Genentech, Immune-Onc, Novartis, and others. A full list of disclosures is published in the editorial. Hasserjian has no financial ties to industry.

Cancer. Published online February 8, 2022. Editorial

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

Source: Read Full Article